Chemistry, Physics, and the Laws of Nature

Imagine one day we explored a part of Mars that no one from Earth had ever visited and we saw rocks that were placed in a formation that read, “This is a message from God. I exist.” We could assign an infinitesimal statistical probability that the formation was caused randomly. We could not, however, assign a statistical probability that there was intelligent design.

Occam’s razor is a problem-solving principle that has often been paraphrased as “the simplest solution is most likely the right one.” What is the simplest solution in this scenario? Just because you can assign a statistical probability, albeit an infinitesimal one, to one answer while you cannot assign one to another answer, doesn’t make the first answer more probable. It makes the comparison incomparable. Intelligent design cannot be measured, but consider whether you think the elegance in its order can be an act of randomness.

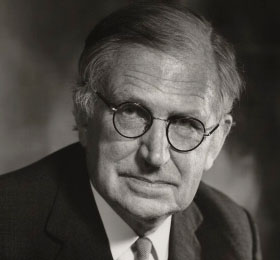

Dr. Gerald Gabrielse

Physicist

Education:

Trinity Christian College

Calvin College, B.S.

University of Chicago, M.S. in Physics, Ph.D. in Physics

University of Washington, Postdoctorate

Quotes

“I do not believe that science and the Bible are in conflict. However, it is possible to misunderstand the Bible and to misunderstand science. It is important to figure out what of each might be misunderstood.”

“My understanding about God clearly does not come from science. I know of no descriptions of God that I can make which lead to predictions that my students and I can test with repeated and verifiable measurements with the methods of science. My science, thus, does not enable me to make scientific statements about God. Based upon the science game that I play, as a scientist I cannot even say that God exists. As a scientist, I also cannot conclude based on my science that God does not exist. I instead learn about God from the Bible.”

Career

Gerald Gabrielse became a postdoc at the University of Washington in Seattle in 1978 under Hans Dehmelt, and joined the faculty in 1985. He became Professor of Physics at Harvard University in 1987, and the chair of the Harvard Physics Department in 2000.

Gabrielse was a pioneer in the field of low energy antiproton and antihydrogen physics by proposing the trapping of antiprotons from a storage ring, cooling them in collisions with trapped electrons, and the use of these to form low energy antihydrogen atoms. He led the TRAP team that realized the first antiproton trapping, the first electron cooling of trapped antiprotons, and the accumulation of antiprotons in a 4 Kelvin apparatus. The demonstrations and methods made possible an effort that grew to involve 4 international collaborations of physicists working at CERN's Antiproton Decelerator. In 1999, Gabrielse's TRAP team made the most precise test of the Standard Model's fundamental CPT theorem by comparing the charge-to-mass ratio of a single trapped antiproton with that of a proton to a precision of 9 parts in 1011. The precision of the resulting confirmation of the Standard Model prediction exceeded that of earlier comparisons by nearly a factor of 106.

Gabrielse now leads the ATRAP team at CERN, one of the two teams that first produced slow antihydrogen atoms and suspended them in a magnetic trap. Both TRAP and ATRAP teams used trapped antiprotons within a nested Penning trap device to produce antihydrogen atoms slow enough to be trapped in a magnetic trap. The team made the first one-particle comparison of the magnetic moments of a single proton and a single antiproton. Their comparison, to a precision of 5 parts per million, was 680 times more precision than previous measurements.

In 2006, Gabrielse's group used a single trapped electron to measure the electron magnetic moment to 0.76 parts per trillion, which was 15 times more precise than a measurement that had stood for about 20 years. Two years later, the team improved the measurement uncertainty by a further factor of 3.

In 2014, Gabrielse, as part of the ACME collaboration with John Doyle at Harvard and David DeMille at Yale, measured the electron electric dipole moment to over an order of magnitude over the previous measurement using a beam of thorium monoxide, a result which had implications for the viability of supersymmetry.

Gabrielse was also one of the discoverers of the Brown-Gabrielse invariance theorem, relating the free space cyclotron frequency to the measureable eigenfrequencies of an imperfect Penning trap. The theorem's applications include precise measurements of magnetic moments and precise mass spectrometry. It also makes sideband mass spectrometry possible, a standard tool of nuclear physics.

Gabrielse has also invented a self-shielding superconducting solenoid that uses flux conservation and a carefully chosen geometry of coupled coils to cancel strong field fluctuations due to external sources. The device was responsible for the success of the precise comparison of antiproton and proton, and also enables magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) systems to locate changing magnetic fields from external sources, such as elevators.

In 2018, Gabrielse moved to Northwestern University, becoming the director of the newly created Center for Fundamental Physics at Low Energy. The center will be the first of its kind to be dedicated to small-scale, tabletop fundamental physics experiments.

Awards

- Fellow of the American Physical Society (1992)

- Distinguished Alumnus Award, Trinity College (1999)

- Levenson Prize for Excellence in the Education of Undergraduates, Harvard University (2000)

- Davisson-Germer Prizeof the American Physical Society (2002)

- George Ledlie Prize, Harvard University (2004)

- Humboldt Research Award, Germany (2005)

- Distinguished Alumni Award, Calvin College (2006)

- Inducted into the National Academy of Sciences (2007)

- Källén Lecturer, Lund, Sweden (2007)

- William H. Zachariasen Lecturer at the University of Chicago (2007-2008)

- Poincaré Lecturer, Paris (2007)

- Premio Caterina Tomassoni and Felice Pietro Chisesi Prize, Italy (2008)

- Julius Edgar Lilienfeld Prize of the American Physical Society (2011)

- Trotter Prize, Texas A&M University (2013)

Katharine Anne Scott Hayhoe

(born April 15, 1972)

Atmospheric Scientist

Education:

University of Toronto, B.S. in Physics and Astronomy

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, M.S. and Ph.D. in Atmospheric Science

Quotes

“From an early age, I just kind of absorbed the idea that science and faith are two sides of the same coin. If you really believe that God created this amazing universe that we live in, then what is science other than trying to figure out what God was thinking when he set the whole thing up in the first place. The Bible defines faith as the evidence of what we don't see. What is science? It's the evidence of what we do see. Science is like a map that tells us which way is north or south or east or west, but it's not the compass that tells us which way is the right way to go.”

Career

Katharine Hayhoe is an atmospheric scientist and professor of political science at Texas Tech University, where she is director of the Climate Science Center. She is also the CEO of the consulting firm ATMOS Research and Consulting.

Hayhoe has worked at Texas Tech since 2005. She has authored more than 120 peer-reviewed publications. She also co-authored some reports for the US Global Change Research Program, as well as some National Academy of Sciences reports, including the 3rd National Climate Assessment, released on May 6, 2014. Shortly after the report was released, Hayhoe said, "Climate change is here and now, and not in some distant time or place," adding that, "The choices we're making today will have a significant impact on our future." She has also served as an expert reviewer for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change's Fourth Assessment Report.

On September 16, 2019 Hayhoe was named one of the United Nations Champions of the Earth in the science and innovation category.

Awards

- United Nations Champions of the Earth, 2019

- Foreign Policy magazine 100 Leading Global Thinkers, 2019

- Stephen H. Schneider Award for Outstanding Science Communication, 2018

- Fortune magazine's 50 World's Great Leaders, 2017

- National Center for Science Education Friend of the Planet award, 2016

- Time magazine's 100 Most Influential People, 2014

- American Geophysical Union Climate Communications Prize, 2014

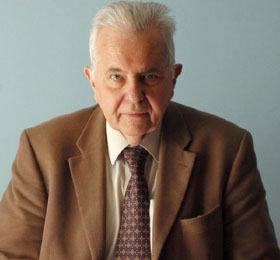

Walter Thirring

(April 29, 1927 – August 19, 2014)

Physicist

Education:

University of Innsbruck, PhD

Quotes

“In the last decades, new worlds have been unveiled that our great teachers wouldn’t have even dreamed of. The panorama of cosmic evolution now enables deep insights into the blueprint of creation… Human beings recognize the blueprints, and understand the language of the Creator… These realizations do not make science the enemy of religion, but glorify the book of Genesis in the Bible.” – Walter Thirring, “Cosmic Impressions”

"Reflections on the creation of the universe lead to reflections about the creator…When we are moved by a fantastic building, a cathedral or a mosque and have finally realized what is behind the glorious proportions, who would then say, ‘Now we don't need the architect anymore. There might not even be one, that could all just be the random product of circumstance.”

Career

Walter Thirring was born in Vienna, Austria, where he earned his Doctor of Physics degree in 1949 at the age of 22. In 1959 he became a professor of theoretical physics at the University of Vienna, and from 1968 to 1971 he was head of the Theory Division and director at CERN.

Besides pioneering work in quantum field theory, Walter Thirring devoted his scientific life to mathematical physics. He is the author of one of the first textbooks on quantum electrodynamics as well as of a four-volume course in mathematical physics.

In 2000, he received the Henri Poincaré Prize of the International Association of Mathematical Physics.

Awards

- xxxxxxx

- Eötvös Medal (1967)

- Erwin Schrödinger Prize (1969)

- Max Planck Medal of the German Physical Society (1978)

- Prize of the city of Vienna (1978)

- Austrian Decoration for Science and Art (1993)

- Honorary Medal of the Austrian capital Vienna in Gold (1993)

- Honorary doctorate from the Comenius University in Bratislava (1994)

- Henri Poincaré Prize of IAMP (International Association of Mathematical Physics) 2000

- Member of the Austrian Academy of Sciences

- Member of the German Academy of Sciences Leopoldina, Halle

- Member of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, Rome

- Member of the National Academy of Sciences, USA

- Member of the Academia Europaea

- Member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences

Selected Works

- xxxxxxx

- Selected papers of Walter E. Thirring with Commentaries. American Mathematical Society, 1998, ISBN 0821808125

- Einführung in die Quantenelektrodynamik. Deuticke, Wien 1955

- o Principles of quantum electrodynamics. Academic Press, New York 1958; 2nd edn. 1962

- with Ernest M. Henley: Elementare Quantenfeldtheorie. BI Verlag, Mannheim 1975

- Erfolge und Misserfolge der theoretischen Physik. In: Physikalische Blätter Jg. 33 (1977), p. 542ff. (Singularitäty theorem of Stephen Hawking and Roger Penrose, KAM-theory, stability of matter, lecture delivered at the presentation of the Max Planck medal)

- Lehrbuch der Mathematischen Physik. Springer (trans. into English by Evans M. Harrell as A course in mathematical physics)

- o 1. Klassische Dynamische Systeme. 1988, ISBN 3-211-82089-2; trans. as Classical dynamical systems[6]

- o 2. Klassische Feldtheorie. 1990, ISBN 3-211-82169-4; trans. as Classical field theory

- o 3. Quantenmechanik von Atomen und Molekülen. 1994, ISBN 3-211-82535-5;[7] trans. as Quantum mechanics of atoms and molecules

- o 4. Quantenmechanik großer Systeme. 1998, ISBN 3-211-81604-6; trans. as Quantum mechanics of large systems

- Stabilität der Materie. In: Naturwissenschaften. Springer, Berlin Jg. 73 (1986), p. 705ff.

- Kosmische Impressionen. Gottes Spuren in den Naturgesetzen. Molden, Wien 2004, ISBN 3-85485-110-3

- Einstein entformelt. Wie ein Teenager ihm auf die Schliche kam. Seifert Verlag, Wien 2007, co-author Cornelia Faustmann, ISBN 3-902-40642-9

- Lust am Forschen: Lebensweg und Begegnungen. Seifert Verlag, Wien 2008, ISBN 978-3902406583

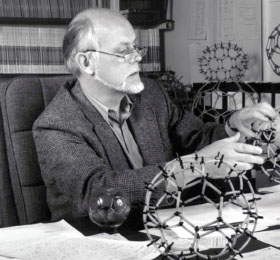

Richard Errett Smalleyp

(June 6, 1943 – October 28, 2005)

Chemist, Physicist

Education:

University of Michigan, B.S.

Princeton University, Ph.D.

University of Chicago, Postdoctoral work

Quotes

“Although I suspect I will never fully understand, I now think the answer is very simple: it’s true. God did create the universe about 13.7 billion years ago.”

At the Tuskegee University's 79th Annual Scholarship Convocation/Parents' Recognition Program he was quoted making the following statement regarding the subject of evolution while urging his audience to take seriously their role as the higher species on this planet. "'Genesis' was right, and there was a creation, and that Creator is still involved ... We are the only species that can destroy the Earth or take care of it and nurture all that live on this very special planet. I'm urging you to look on these things. For whatever reason, this planet was built specifically for us. Working on this planet is an absolute moral code. ... Let's go out and do what we were put on Earth to do."

Career

Richard Smalley was the Gene and Norman Hackerman Professor of Chemistry and a Professor of Physics and Astronomy at Rice University, in Houston, Texas. In 1996, along with Robert Curl, also a professor of chemistry at Rice, and Harold Kroto, a professor at the University of Sussex, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the discovery of a new form of carbon, buckminsterfullerene, also known as buckyballs. He was an advocate of nanotechnology and its applications.

Awards

- xxxxxxx

- Irving Langmuir Prize in Chemical Physics, American Physical Society, 1991

- Popular Science Magazine Grand Award in Science & Technology, 1991

- APS International Prize for New Materials, 1992 (Joint with R. F. Curl & H. W. Kroto)

- Ernest O. Lawrence Memorial Award, U.S. Department of Energy, 1992

- Welch Award in Chemistry, Robert A. Welch Foundation, 1992

- Auburn-G.M. Kosolapoff Award, Auburn Section, American Chemical Society, 1992

- Southwest Regional Award, American Chemical Society, 1992

- William H. Nichols Medal, New York Section, American Chemical Society, 1993

- The John Scott Award, City of Philadelphia, 1993

- Hewlett-Packard Europhysics Prize, European Physical Society, 1994 (with Wolfgang Kraetschmer, Don Huffman and Harold Kroto)

- Harrison Howe Award, Rochester Section, American Chemical Society, 1994

- Madison Marshall Award, North Alabama Section, American Chemical Society, 1995

- Franklin Medal, The Franklin Institute, 1996

- Nobel Prize in Chemistry, Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, 1996

- Distinguished Civilian Public Service Award, Department of the Navy, 1997

- American Carbon Society Medal, 1997

- Top 75 Distinguished Contributors, Chemical & Engineering News, 1998

- Lifetime Achievement Award, Small Times Magazine, 2003

- Glenn T. Seaborg Medal, University of California at Los Angeles, 2002

- Distinguished Alumni Award, Hope College, 2005

- 50th Anniversary Visionary Award, SPIE – International Society for Optical Engineering, 2005

- National Historic Chemical Landmark, American Chemical Society, 2010

- Citation for Chemical Breakthrough Award, Division of History of Chemistry, American Chemical Society, 2015

Selected Works

- Smalley, R.E. "Supersonic bare metal cluster beams. Final report", Rice University, United States Department of Energy—Office of Energy Research, (Oct. 14, 1997).

- Smalley, R.E. "Supersonic Bare Metal Cluster Beams. Technical Progress Report, March 16, 1984 - April 1, 1985", Rice University, United States Department of Energy—Office of Basic Energy Sciences, (Jan. 1, 1985).

Sir Nevill Francis Mott

(September, 30 1905 – August 8, 1996)

Physicist

Education:

St. John’s College, Cambridge

Quotes

“Science can have a purifying effect on religion, freeing it from beliefs from a pre-scientific age and helping us to a truer conception of God. At the same time, I am far from believing that science will ever give us the answers to all our questions.”

Career

Nevill Francis was a British physicist who won the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1977 for his work on the electronic structure of magnetic and disordered systems, especially amorphous semiconductors. The award was shared with Philip W. Anderson and J. H. Van Vleck. The three had conducted loosely related research. Mott and Anderson clarified the reasons why magnetic or amorphous materials can sometimes be metallic and sometimes insulating.

Awards

- In 1977, Nevill Mott was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics, together with Philip Warren Anderson and John Hasbrouck Van Vleck "for their fundamental theoretical investigations of the electronic structure of magnetic and disordered systems." The news of having won the Nobel Prize received Mott while having lunch at restaurant Die Sonne in Marburg, Germany, during a visit to fellow solid state scientist at Marburg University.

- Mott was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1936. Mott served as president of the Physical Society in 1957. In the early 1960s he was chairman of the British Pugwash group. He was knighted in 1962.

- Mott received an honorary Doctorate from Heriot-Watt University in 1972.

- In 1981, Mott became a founding member of the World Cultural Council.

- He continued to work until he was about ninety. He was made a Companion of Honour in 1995.

- In 1995, Mott visited the Loughborough University Department of Physics and presented a lecture entitled "65 Years in Physics." The University continues to host the annual Sir Nevill Mott Lecture.

Selected Works

-

N. F. Mott revived the old Philosophical Magazine and transformed it into a lively publication essentially centred on the then-new field of solid state physics, attracting writers, readers and general interest on a wide scale. After receiving a paper on point defects in crystals by Frederick Seitz that was obviously too long for Phil. Mag, Mott decided to create a new publication, Advances in Physics for such review papers. Both publications are still active in 2017.

- N. F. Mott, "The Wave Mechanics of α-Ray Tracks", Proceedings of the Royal Society (1929) A126, pp. 79–84, doi:10.1098/rspa.1929.0205. (reprinted as Sec.I-6 of Quantum Theory and Measurement, J. A. Wheeler. and W. H. Zurek, (1983) Princeton).

- N. F. Mott, Metal-Insulator Transitions, second edition (Taylor & Francis, London, 1990). ISBN 0-85066-783-6, ISBN 978-0-85066-783-7

- N. F. Mott, A Life in Science (Taylor & Francis, London, 1986). ISBN 0-85066-333-4, ISBN 978-0-85066-333-4

- N. F. Mott, H. Jones, The Theory of Properties of Metals and Alloys, (Dover Publications Inc., New York, 1958)

- Brian Pippard, Nevill Francis Mott, Physics Today, March 1997, pp. 95 and 96: (pdf).

Nicola Cabibbo

(April 10, 1935 – August 16, 2010)

Physicist

Education:

Universita di Roma

Quotes

“If the will of God was to create man, he certainly organized things in a beautiful way to do it. Of course, we know by revelation that God wanted to create man, but we don't know how he did it. This is what science attempts to explain. There cannot be any clash or controversy between science and religion, because they work on different planes.”

Career

Nicola Cabibbo graduated in theoretical physics at the Università di Roma "Sapienza University of Rome" in 1958 under the supervision of Bruno Touschek. In 1963, while working at CERN, Cabibbo found the solution to the puzzle of the weak decays of strange particles, formulating what came to be known as Cabibbo universality. In 1967 Nicola settled back in Rome where he taught theoretical physics and created a large school with younger colleagues and brilliant students. He was president of the INFN from 1983 to 1992, during which time the Gran Sasso Laboratory was inaugurated. He was also president of the Italian energy agency, ENEA, from 1993 to 1998, and was president of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences from 1993 until his death. In 2004, Cabibbo spent a year at CERN as guest professor, joining the NA48/2 collaboration.

Selected Works

Cabibbo's major work on the weak interaction originated from a need to explain two observed phenomena:

- The transitions between up and down quarks, between electrons and electron neutrinos, and between muons and muon neutrinos had similar likelihood of occurring (similar amplitudes); and

- The transitions with change in strangeness had amplitudes equal to one fourth of those with no change in strangeness.

Ernest Thomas Sinton Walton

(October 6, 1903 – June 25, 1995)

Physicist

Education:

Trinity College Dublin, Bachelor and Master’s degrees

Trinity College Cambridge, Ph.D.

Quotes

"One way to learn the mind of the Creator is to study His creation. We must pay God the compliment of studying His work of art and this should apply to all realms of human thought. A refusal to use our intelligence honestly is an act of contempt for Him who gave us that intelligence."

Career

Ernest Walton was a British-Irish physicist and Nobel laureate for his work with John Cockcroft with "atom-smashing" experiments done at Cambridge University in the early 1930s, and so became the first person in history to split the atom.

Walton and John Cockcroft collaborated to build an apparatus that split the nuclei of lithium atoms by bombarding them with a stream of protons accelerated inside a high-voltage tube (700 kilovolts). The splitting of the lithium nuclei produced helium nuclei. This was experimental verification of theories about atomic structure that had been proposed earlier by Rutherford, George Gamow, and others. The successful apparatus – a type of particle accelerator now called the Cockcroft-Walton generator – helped to usher in an era of particle-accelerator-based experimental nuclear physics. It was this research at Cambridge in the early 1930s that won Walton and Cockcroft the Nobel Prize in physics in 1951.

Walton was associated with the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies for over 40 years, e.g., serving long periods on the board of the School of Cosmic Physics and on the Council of the Institute. Following the 1952 death of John J. Nolan, the inaugural chairman of the School of Cosmic Physics, Walton assumed the role, and served in that position until 1960, when he was succeeded by John H. Poole.

Christian Boehmer Anfinsen Jr.

(March 26, 1916 – May 14, 1995)

Biochemist

Education:

Swarthmore College, BA

University of Pennsylvania, MS in Organic Chemistry

Harvard Medical School, PhD

Quotes

“I think only an idiot can be an atheist. We must admit that there exists an incomprehensible power or force with limitless foresight and knowledge that started the whole universe going in the first place.”

Career

In 1950, the National Heart Institute, part of the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, recruited Anfinsen as chief of its laboratory of cell physiology. In 1954, a Rockefeller Foundation fellowship enabled Anfinsen to return to the Carlsberg Laboratory for a year and a Guggenheim Foundation fellowship allowed him to study at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel from 1958 to 1959. He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1958.

In 1962, Anfinsen returned to Harvard Medical School as a visiting professor and was invited to become chair of the department of chemistry. He was subsequently appointed chief of the laboratory of chemical biology at the National Institute of Arthritis and Metabolic Diseases (now the National Institute of Arthritis, Diabetes, and Digestive and Kidney Diseases), where he remained until 1981. In 1981, Anfinsen became a founding member of the World Cultural Council. From 1982 until his death in 1995, Anfinsen was professor of biophysical chemistry at Johns Hopkins.

Anfinsen published more than 200 original articles, mostly in the area of the relationships between structure and function in proteins. He was also a pioneer of ideas in the area of nucleic acid compaction. In 1961, he showed that ribonuclease could be refolded after denaturation while preserving enzyme activity, thereby suggesting that all the information required by protein to adopt its final conformation is encoded in its amino-acid sequence. He belonged to the National Academy of Sciences (USA), the Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters and the American Philosophical Society

Selected Works

- The Molecular Basis of Evolution (1959)

- Advances In Protein Chemistry (1980)

Gerhard Ertl

(born October 10, 1936)

Physicist

Education:

Technical University of Stuttgart, Diplom in Physics

University of Paris

Ludwig Maximilian University

Technical University of Munich, Ph.D.

Quotes

“I believe in God. I am a Christian and I try to live as a Christian. I read the Bible very often and I try to understand it.”

Career

Gerhard Ertl is a German physicist and a Professor emeritus at the Department of Physical Chemistry, Fritz-Haber-Institut der Max-Planck-Gesellschaft in Berlin, Germany. Ertl's research laid the foundation of modern surface chemistry, which has helped explain how fuel cells produce energy without pollution, how catalytic converters clean up car exhausts and even why iron rusts, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences said.

His work has paved the way for development of cleaner energy sources and will guide the development of fuel cells, said Astrid Graslund, secretary of the Nobel Committee for Chemistry.

He was awarded the 2007 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his studies of chemical processes on solid surfaces. The Nobel academy said Ertl provided a detailed description of how chemical reactions take place on surfaces. His findings applied in both academic studies and industrial development, the academy said. “Surface chemistry can even explain the destruction of the ozone layer, as vital steps in the reaction actually take place on the surfaces of small crystals of ice in the stratosphere,” the award citation reads.

Awards

- Japan Prize (1992)

- Wolf Prize in Chemistry (1998)

- Nobel Prize in Chemistry (2007)

- Otto Hahn Prize (2007)

- Faraday Lectureship Prize (2007)

Gerty Theresa Cori

(née Radnitz; August 15, 1896 – October 26, 1957)

Biochemist

Education:

Karl-Ferdinands-Universität in Prague

Quotes

Gerty Cori was a Jewish Austro-Hungarian-American biochemist who in 1947 was the third woman—and first American woman—to win a Nobel Prize in science, and the first woman to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, for her role in the discovery of glycogen metabolism.

Cori was born in Prague (then in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, now the Czech Republic). Gerty was not a nickname, but rather she was named after an Austrian warship. Growing up at a time when women were marginalized in science and allowed few educational opportunities, she gained admittance to medical school, where she met her future husband Carl Ferdinand Cori in an anatomy class;[4] upon their graduation in 1920, they married. Because of deteriorating conditions in Europe, the couple emigrated to the United States in 1922. Gerty Cori continued her early interest in medical research, collaborating in the laboratory with Carl. She published research findings coauthored with her husband, as well as publishing singly. Unlike her husband, she had difficulty securing research positions, and the ones she obtained provided meager pay. Her husband insisted on continuing their collaboration, though he was discouraged from doing so by the institutions that employed him.

With her husband Carl and Argentine physiologist Bernardo Houssay, Gerty Cori received the Nobel Prize in 1947 for the discovery of the mechanism by which glycogen—a derivative of glucose—is broken down in muscle tissue into lactic acid and then resynthesized in the body and stored as a source of energy (known as the Cori cycle). They also identified the important catalyzing compound, the Cori ester. In 2004, both Gerty and Carl Cori were designated a National Historic Chemical Landmark in recognition of their work in clarifying carbohydrate metabolism.

Awards

In 1947, Gerty Cori became the third woman—and the first American woman—to win a Nobel Prize in science, the previous recipients being Marie Curie and Irène Joliot-Curie. She was the first woman to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. She was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1953. Cori was the fourth women elected to the National Academy of Sciences. She was appointed by President Harry S. Truman as board member of the National Science Foundation, a position she held until her death.

Gerty was also a member of the American Society of Biological Chemists, the American Chemical Society and the American Philosophical Society. She and her husband were presented jointly with the Midwest Award (American Chemical Society) in 1946 and the Squibb Award in Endocrinology in 1947. In addition, Cori received the Garvan-Olin Medal (1948), the St. Louis Award (1948), the Sugar Research Prize (1950), the Borden Award (1951).[22] She received honorary Doctor of Science degrees from Boston University (1948), Smith College (1949), Yale University (1951), Columbia University (1954), and the University of Rochester (1955).

The twenty-five square foot laboratory shared by Cori and her husband at Washington University was deemed a National Historic Landmark by the American Chemical Society in 2004. Six of the scientists mentored by Cori and her husband went on to win Nobel Prizes, which is only superseded by the mentored scientists of British physicist J.J. Thomson.

In 1949, she was awarded the Iota Sigma Pi National Honorary Member for her significant contribution. The crater Cori on the Moon is named after her, as is the Cori crater on Venus. She shares a star with her husband on the St. Louis Walk of Fame. She was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame in 1998.

Cori was honored by the release of a US Postal Service stamp in April 2008. The 41-cent stamp was reported by the Associated Press to have a printing error in the chemical formula for glucose-1-phosphate (Cori ester), but was distributed despite the error. Her description reads: "Biochemist Gerty Cori (1896–1957), in collaboration with her husband, Carl, made important discoveries—including a new derivative of glucose—that elucidated the steps of carbohydrate metabolism and contributed to the understanding and treatment of diabetes and other metabolic diseases. In 1947, the couple was awarded a half share of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine."

The US Department of Energy named the NERSC-8 supercomputer installed at Berkeley Lab in 2015/2016 after Cori. In November 2016, NERSC's Cori ranked 5th on the TOP500 list of world's most powerful high-performance computers.

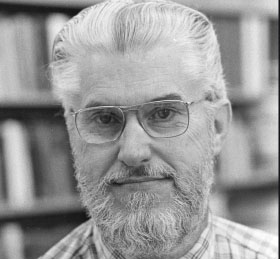

Richard H. Bube

(August 10, 1927 – June 9, 2018)

Physicist

Education:

Brown University, B.S. in Physics

Princeton University, M.A. and Ph.D. in Physics

Career

He was a researcher at RCA Laboratories in Princeton, New Jersey from 1948 to 1962. Thereafter he taught at Stanford University where he was an associate professor from 1962 to 1964, when he became professor of materials science and electrical engineering. He served as his department's chair from 1975 to 1986, and is now an emeritus professor.

For over twenty years he also conducted an undergraduate seminar at Stanford University on "Issues in Science and Christianity," until it was canceled in 1988 by Stanford University.

Selected Works

- Electrons in solids : an introductory survey (1982, 1992), Richard H Bube

- Photoconductivity of solids (1960, 1978)

- Fundamentals of solar cells : photovoltaic solar energy conversion co-authored with Alan L Fahrenbruch(1983)

- Electronic properties of crystalline solids: an introduction to fundamentals (1974)

- Photoelectronic properties of semiconductors by Richard H Bube (1992)

- Photovoltaic materials (1998), ISBN 1-86094-065-X

- Photoinduced defects in semiconductors co-authored with David Redfield (1996)

- Annual review of materials science (1971-onward)

- Putting it all Together: Seven Patterns for Relating Science and the Christian faith. University Press of America, 1995. ISBN 0-8191-9755-6.

- The Encounter between Christianity and Science (1968)

- The Human Quest: a New Look at Science and the Christian Faith (1971, 1976)

- To Every Man an Answer: a Systematic study of the Scriptural basis of Christian Doctrine (1955)

- One Whole Life. (self-published autobiography). 530 pages. 1995.

- "Man in the Context of Evolutionary Theory". Horizons of science : Christian scholars speak out. Ed. Carl F. H. Henry. Harper & Row, 1978. ISBN 0-06-063866-4.

- "Scientist as Believer". Expanding humanity's vision of God : new thoughts on science and religion. Ed. Robert L. Herrmann. Templeton Foundation Press, 2001. ISBN 1-890151-50-5.

- "Postscript: Final Reflections on the Dialogue". Summaries by Richard H. Bube and Phillip E. Johnson. Three Views on Creation and Evolution. pp. 249–266. Zondervan, 1999. ISBN 0-310-22017-3.